About Fort Bragg

It’s discernable, the welcome sense of remoteness that comes over you in Fort Bragg. And with that distance from the ordinary comes a certain kind of freedom that you won’t find in many California coast towns. It’s a place where you can hike and bike, wine and dine, kayak and beachcomb. But even with so much to experience, there’s another reason people love coming back to Fort Bragg year after year. Call it North Coast Hospitality, but there’s a unique sense of neighborliness here, a lack of pretension and a spirit of community that stays with you even when the scent of fresh ocean air has faded.

Fort Facts & Oddities

The City of Fort Bragg was founded as a military garrison in 1857 and incorporated in 1889.

That boxy-looking building south of Glass Beach. It’s the old lumber company’s dynamite shed. Trespassing is strongly discouraged.

Fort Bragg’s sister city, at the exact same latitude, is Otsuchi, Japan which was devasted by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

The Skunk Train got its name in the 1920s when self-powered, yellow rail cars were introduced. The locals called them Skunks because you could “smell ‘em before you see ‘em.”

The beautiful First Baptist Church at Pine & Franklin Street was rotated 90 degrees and rebuilt after the bell tower collapsed in 1926.

See if you can find the old horse and buggy hitching rings that still exist on curbs around town. There are at least 10 of them.

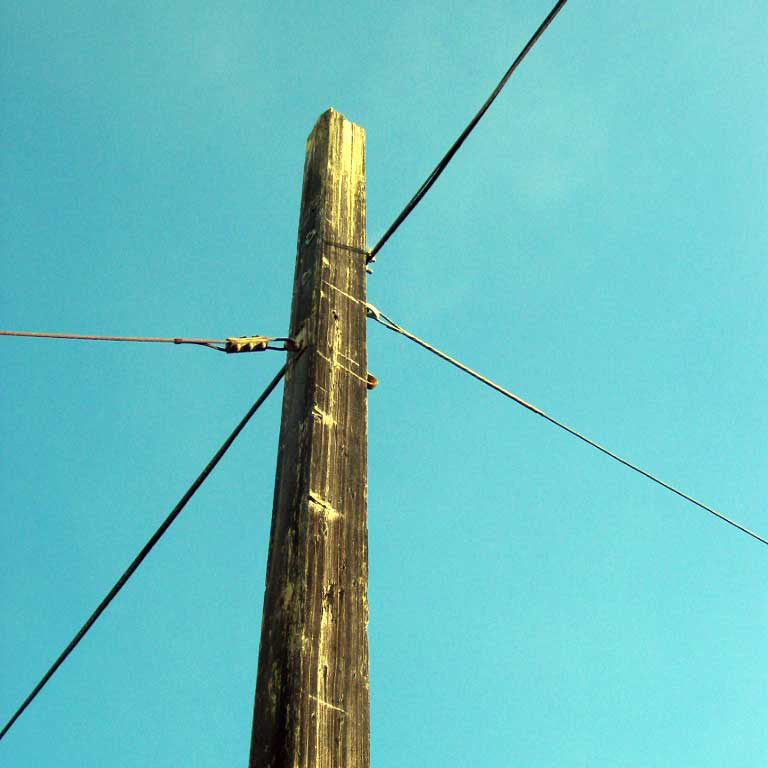

Impress your friends by pointing out the only two redwood power poles from the days when the mill provided power. One is at Laurel & Harrison Streets, the other is by Laurel and Harold.

In the old graveyard at the end of Spruce Street, if you know where to look, two survivors of the Donner Party are buried.

History

The people of Fort Bragg are committed to presenting an honest and unvarnished representation of our city’s past and founding.

Below is a highly-condensed timeline documenting pivotal moments in Fort Bragg history.

First People

First People

For thousands of years before European settlers, the area in and around Fort Bragg was home to one of North America’s densest and most diverse populations of native peoples, with Pomo being the largest native culture in the area. While most tribal bands lived inland, they frequented the coast to collect shellfish, seaweed, salt and other resources. Go deeper at the Fort Bragg-Mendocino Coast Historical Society.

The first white settlers in what is now Fort Bragg came as an exploration party from the US Bureau of Indian Affairs to establish a reservation. In the name of “settlement” indigenous people were uprooted, interned, enslaved, relocated and subject to often inhumane conditions. By 1866 the natives had all been forcibly displaced and the Reservation was discontinued.

In the summer of 1857, 1st Lt. Horatio Gibson, then serving at the Presidio of San Francisco, established a military post on the reservation, naming it after his former commanding officer in the Mexican-American War, Capt. Braxton Bragg. Bragg, who later became a General in the Army of the Confederacy, was a native of North Carolina and a slave owner. He never visited the California city that bore his name.

With two partners, C.R. Johnson moved his mill on the Ten Mill River to take advantage of the Noyo River harbor, incorporating as the Fort Bragg Redwood Lumber Company, later renamed the Union Lumber Company. That same year the Fort Bragg Railroad was created to carry redwood logs from the forest to Fort Bragg.

The documents of incorporation show C.R. Johnson as Mayor with Fort Bragg’s plat maps drafted by one Calvin Stewart.

Fishing has, and likely always will be, an integral part of life in Fort Bragg and Noyo Harbor is one of only four California harbors north of San Francisco. The first salmon fishery was noted in 1898 and motorized trollers led to salmon canneries opening along the Noyo River in the 1920s. Today’s current climatic conditions and river diversions have led to a near decimation of the habitat that supports salmon and other commercial and sport fishing species.

Fort Bragg was severely damaged during the great earthquake of 1906. Most brick buildings collapsed and fire ravaged the town. However, the local mills benefited providing lumber to rebuild San Francisco. Bricks used as ballast for arriving ships were used help rebuild damaged Fort Bragg buildings.

Now called the California Western Railroad, the line to Willits was completed. Visitors could easily visit Fort Bragg via what eventually became the Skunk Train. By 1916 Fort Bragg was a popular destination to visit and to settle.

The Union Lumber Company was purchased by Boise Cascade and in 1973 became part of Georgia Pacific Lumber Company, one of the world’s largest manufacturers and distributors of paper products. The mill was closed in 2002. Currently, much of the mill site along the Fort Bragg coastline has been sold and is undergoing redevelopment.